About Adverse Childhood Experiences

What are adverse childhood experiences?

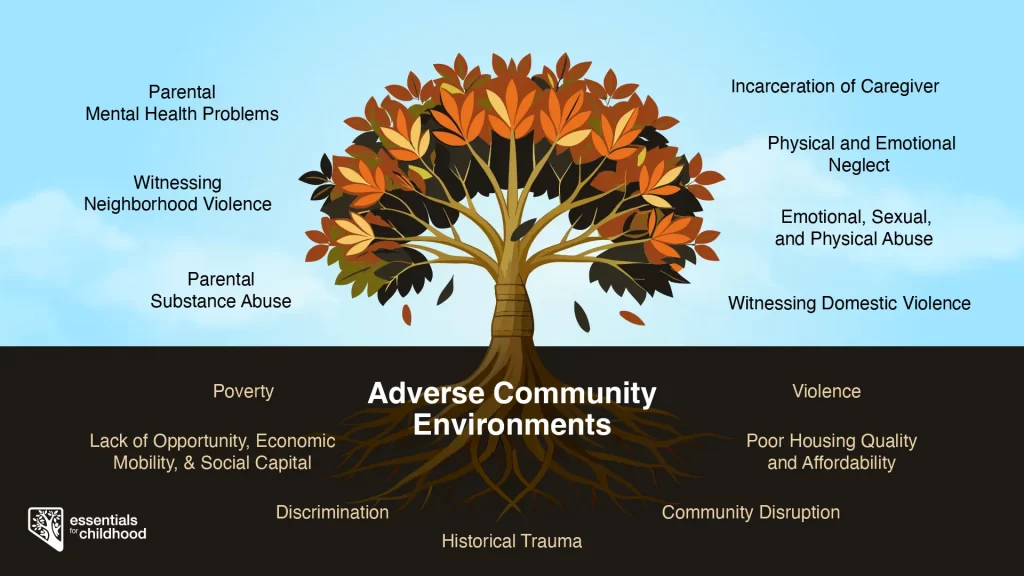

Adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs, are disruptions to the promotion of safe, stable, and nurturing family relationships and are characterized by stressful or traumatic events that occur during an individual’s first 18 years of life. ACEs can occur at home (such as abuse, neglect, or household challenges), at school (such as bullying or school violence victimization), with peers (such as physical and sexual dating violence), or within the community (such as witnessing community violence). These individual-level ACEs can create ‘toxic stress’ within youth and lead to negative health and behavioral outcomes. [1] Youth with exposure to multiple ACEs often have worse health and behavioral outcomes.

Social conditions may also create toxic stress. The social determinants of health (SDOH) a child encounters may also be a source of adversity and stress. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) describes SDOH as “the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, worship, and age. These conditions include a wide set of forces and systems that shape daily life such as economic policies and systems, social norms, social policies, and political systems.” [2] SDOH examples include unemployment, lack of access to health care, childhood poverty, and poor housing quality.

Figure Title: Adverse childhood experiences at the individual and community level

How prevalent are adverse childhood experiences in Nevada?

According to the 2023 Nevada Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), nearly three in four (73.3%) of Nevada middle school students have experienced one or more ACE, and 14.3% experienced four or more ACEs. [3] Over three fourths (77.4%) of Nevada high school students have experienced one or more ACE, and one in five (21.2%) experienced four or more ACEs. [4]

Middle School

High School

Figure Title: Prevalence of ACEs among Nevada’s secondary students, 2023 YRBS

Middle School

High School

Figure Title: Prevalence of individual ACEs among Nevada’s secondary students, 2023 YRBS

Who is at greater risk for adverse childhood experiences in Nevada?

While all children are at risk for ACEs, numerous studies show inequities in such experiences. In Nevada, ACEs are highest among sexual and gender minority youth, children living in rural and frontier regions, Great Basin tribes, and children living in military households.

Sexual minority middle school students are more likely to report having four or more ACEs (range of 19.6% for gay/lesbian youth to 31.8% for bisexual youth), compared to 11.0% of heterosexual students (p<0.001). [3] The same is true for sexual minority high school students, as they have a higher prevalence of four or more ACEs (range of 26.1% for questioning youth to 40.5% for bisexual youth), compared to 16.1% of heterosexual youth (p<0.001). [4] Additionally, sexual minority high school students who experience a high level of ACEs had approximately 13 times higher odds suicide ideation and attempts in the past 12 months. [5] Gender minority students also experience health disparities and a disproportionate burden of ACEs. Gender minority middle school students also have a higher prevalence of reporting four or more ACEs (33.1% of transgender youth), compared to 13.8% of cisgender youth (p<0.001); [3] similarly, 45.9% of high school transgender students reported four or more ACEs, compared to 19.8% of cisgender students (p<0.001). [4]

Fourteen of Nevada’s 17 counties are classified as rural or frontier. While these counties do not make up the majority of the state’s population, children and youth living in these counties experience higher ACE exposure. Among Nevada’s middle school population, 18.1% of students in rural counties and 18.6% of students in frontier counties reported four or more ACEs compared to 13.9% of students in urban counties (p<0.001). [3] Among Nevada’s high school population, 29.2% of students in rural counties and 24.7% of students in frontier counties reported four or more ACEs compared to 20.7% of students in urban counties (p=0.012). [4]

Nevada is home to the Great Basin Tribes of the Numu (Northern Paiute), Newe (Western Shoshone), Nuwu (Southern Paiute) and the Wašiw (Washoe). These communities are comprised of 28 separate reservations, bands, colonies, and community councils. The health disparities experienced by indigenous youth in our communities reflect a national crisis rooted in historical trauma. American Indian and Alaska Native middle and high school students have the highest ACE exposure, and prevalence of some ACEs (e.g., witnessing domestic violence, physical abuse, and household substance use) is particularly high among students attending tribal schools. [6]

Approximately 40% of adults in the U.S. military have children and most of these children will attend civilian schools.14 Among Nevada’s middle school population, 23.8% of students in military households experienced four or more ACEs compared to 13.5% of students who did not have a parent on active military duty (p<0.001). [3] Additionally, cumulative exposure to ACEs completely mediated the relationship between military family involvement and attempted suicide among high school students. [7]

What are the effects of chronic ACE exposure?

ACEs can have lasting effects on health outcomes across the lifespan. In Nevada, there is a strong and graded relationship between ACE exposure and poor mental health and substance use outcomes among youth. [8;9;10;11;12] Further, youth with ACE exposure experience an increased clustering of high-risk behaviors when compared to youth with no ACE exposure. [8]

The health outcomes associated with ACEs expand into adulthood. In Nevada, ACE exposure during childhood is associated with marijuana and alcohol use during pregnancy [13;14] and female prisoners who reported higher ACE exposure had increased odds of future suicide attempts. [15]

What is the cost of adverse childhood experiences?

ACEs are costly. ACEs-related health consequences cost an estimated economic burden of $748 billion annually in North America.

Preventing ACEs could potentially reduce many health conditions. Estimates show up to 1.9 million heart disease cases and 21 million depression cases potentially could have been avoided by preventing ACEs. [18] Preventing ACEs could reduce suicide attempts among high school students by as much as 89%, sexual intercourse without a condom by as much as 64%, prescription pain medication misuse by as much as 84%, and electronic vapor product use by as much as 73%. [19]

How can adverse childhood experiences be prevented?

Preventing adverse childhood experiences requires understanding and addressing the factors that put people at risk for or protect them from violence.

ACE prevention strategies include parenting classes, social-emotional learning, increased social support, and social service referrals. [20;21] At a policy level, effective ACE prevention strategies include increasing economic supports through programs such as state-level Earned Income Tax Credits (EITC) [22;23;24], increasing access to quality early child care and education [25;26;27], and reducing the numbers of uninsured children [28].

Creating safe, stable, nurturing relationships and environments for all children prevent ACEs and help all children reach their full potential. These relationships and environments are essential to creating positive childhood experiences. We all have a role to play.

In Nevada, we are working to prevent ACEs through campaigns to reduce stigma around parent help-seeking behaviors and increasing family-friendly work policies in. Learn more about Nevada’s prevention strategies.

Learn more about adverse childhood experiences:

References

- Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. (2025, March 13). Toxic stress: What is toxic stress? https://developingchild.harvard.edu/key-concept/toxic-stress/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, January 11). Social Determinants of Health (SDOH). https://www.cdc.gov/about/priorities/why-is-addressing-sdoh-important.html

- Powers, M., Howard, L., Zhang, F., Peek, J., Clements-Nolle, K., Yang, W. (2024). University of Nevada, Reno School of Public Health and State of Nevada, Division of Public and Behavioral Health. 2023 Nevada Middle School Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS): Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Special Report.

- Powers, M., Howard, L., Zhang, F., Peek, J., Clements-Nolle, K., Yang, W. (2024). University of Nevada, Reno School of Public Health and State of Nevada, Division of Public and Behavioral Health. 2023 Nevada High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS): Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Special Report.

- Clements-Nolle K, Lensch T, Baxa A, Gay C, Larson S, Yang W. Sexual Identity, Adverse Childhood Experiences, and Suicidal Behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 2018 Feb;62(2):198-204. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.09.022. Epub 2017 Dec 6. PMID: 29223563; PMCID: PMC5803435.

- Lensch, T., Martin, H.K., Zhang, F., Peek, J., Larson, S., Clements-Nolle, K., Yang, W. State of Nevada, Division of Public and Behavioral Health and the University of Nevada, Reno. 2017 Nevada High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS): American Indian / Alaska Native Report.

- Clements-Nolle K, Lensch T, Yang Y, Martin H, Peek J, Yang W. Attempted Suicide Among Adolescents in Military Families: The Mediating Role of Adverse Childhood Experiences. J Interpers Violence. 2021 Dec;36(23-24):11743-11754. doi: 10.1177/0886260519900976. Epub 2020 Jan 24. PMID: 31976794.

- Diedrick M, Clements-Nolle K, Anderson M, Yang W. Adverse childhood experiences and clustering of high-risk behaviors among high school students: a cross-sectional study. Public Health. 2023 Aug;221:39-45. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2023.05.020. Epub 2023 Jun 30. PMID: 37393751.

- Lensch T, Drake C, Clements-Nolle K, Pearson J. Multilevel Risk and Protective Factors for Frequent and Nonfrequent Past-30-Day Marijuana Use: Findings From a Representative Sample of High School Youth. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2023 Jul;84(4):508-519. doi: 10.15288/jsad.22-00240. Epub 2023 Feb 22. PMID: 36971761; PMCID: PMC10488312.

- Clements-Nolle KD, Lensch T, Drake CS, Pearson JL. Adverse childhood experiences and past 30-day cannabis use among middle and high school students: The protective influence of families and schools. Addict Behav. 2022 Jul;130:107280. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107280. Epub 2022 Feb 14. PMID: 35279622; PMCID: PMC9223419.

- Lensch T, Clements-Nolle K, Oman RF, Evans WP, Lu M, Yang W. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Suicidal Behaviors Among Youth: The Buffering Influence of Family Communication and School Connectedness. J Adolesc Health. 2021 May;68(5):945-952. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.024. Epub 2020 Oct 8. PMID: 33039270.

- Williams L, Clements-Nolle K, Lensch T, Yang W. Exposure to adverse childhood experiences and early initiation of electronic vapor product use among middle school students in Nevada. Addict Behav Rep. 2020 Feb 19;11:100266. doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100266. PMID: 32467855; PMCID: PMC7244918.

- Thomas SA, Clements-Nolle KD, Wagner KD, Omaye S, Lu M, Yang W. Adverse childhood experiences, antenatal stressful life events, and marijuana use during pregnancy: A population-based study. Prev Med. 2023 Sep;174:107656. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2023.107656. Epub 2023 Aug 3. PMID: 37543311.

- Frankenberger DJ, Clements-Nolle K, Yang W. The Association between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Alcohol Use during Pregnancy in a Representative Sample of Adult Women. Womens Health Issues. 2015 Nov-Dec;25(6):688-95. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2015.06.007. Epub 2015 Jul 27. PMID: 26227209; PMCID: PMC4641834.

- Clements-Nolle, K., Wolden, M., & Bargmann-Losche, J. (2009). Childhood trauma and risk for past and future suicide attempts among women in prison. Women’s Health Issues, 19(3), 185–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2009.02.002

- Bellis MA, Hughes K, Ford K, Ramos Rodriguez G, Sethi D, Passmore J. Life course health consequences and associated annual costs of adverse childhood experiences across Europe and North America: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2019 Oct;4(10):e517-e528. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30145-8. Epub 2019 Sep 3. PMID: 31492648; PMCID: PMC7098477.

- Peterson C, Aslam MV, Niolon PH, Bacon S, Bellis MA, Mercy JA, Florence C. Economic Burden of Health Conditions Associated With Adverse Childhood Experiences Among US Adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Dec 1;6(12):e2346323. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.46323. PMID: 38055277; PMCID: PMC10701608.

- Merrick MT, Ford DC, Ports KA, Guinn AS, Chen J, Klevens J, Metzler M, Jones CM, Simon TR, Daniel VM, Ottley P, Mercy JA. Vital Signs: Estimated Proportion of Adult Health Problems Attributable to Adverse Childhood Experiences and Implications for Prevention – 25 States, 2015-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Nov 8;68(44):999-1005. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6844e1. PMID: 31697656; PMCID: PMC6837472.

- Swedo EA, Pampati S, Anderson KN, et al. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Health Conditions and Risk Behaviors Among High School Students — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2023. MMWR Suppl 2024;73(Suppl-4):39–49. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su7304a5

- Hustedde C. Adverse Childhood Experiences. Prim Care. 2021 Sep;48(3):493-504. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2021.05.005. Epub 2021 Jul 10. PMID: 34311853.

- Marie-Mitchell A, Kostolansky R. A Systematic Review of Trials to Improve Child Outcomes Associated With Adverse Childhood Experiences. Am J Prev Med. 2019 May;56(5):756-764. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.11.030. Epub 2019 Mar 21. PMID: 30905481.

- Rostad WL, Ports KA, Tang S, Klevens J. Reducing the Number of Children Entering Foster Care: Effects of State Earned Income Tax Credits. Child Maltreat. 2020 Nov;25(4):393-397. doi: 10.1177/1077559519900922. Epub 2020 Jan 24. PMID: 31973550; PMCID: PMC7377953.

- Kovski NL, Hill HD, Mooney SJ, Rivara FP, Morgan ER, Rowhani-Rahbar A. Association of State-Level Earned Income Tax Credits With Rates of Reported Child Maltreatment, 2004-2017. Child Maltreat. 2022 Aug;27(3):325-333. doi: 10.1177/1077559520987302. Epub 2021 Jan 19. PMID: 33464121; PMCID: PMC8286976.

- Klevens J, Schmidt B, Luo F, Xu L, Ports KA, Lee RD. Effect of the Earned Income Tax Credit on Hospital Admissions for Pediatric Abusive Head Trauma, 1995-2013. Public Health Rep. 2017 Jul/Aug;132(4):505-511. doi: 10.1177/0033354917710905. Epub 2017 Jun 13. PMID: 28609181; PMCID: PMC5507428.

- Klevens J, Barnett SB, Florence C, Moore D. Exploring policies for the reduction of child physical abuse and neglect. Child Abuse Negl. 2015 Feb;40:1-11. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.07.013. Epub 2014 Aug 12. PMID: 25124051; PMCID: PMC4689429.

- Klein, S. (2011). The Availability of Neighborhood Early Care and Education Resources and the Maltreatment of Young Children. Child Maltreatment, 16(4), 300-311. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559511428801 (Original work published 2011)

- Mersky JP, Topitzes JD, Reynolds AJ. Maltreatment prevention through early childhood intervention: A confirmatory evaluation of the Chicago Child-Parent Center preschool program. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2011 Aug;33(8):1454-1463. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.04.022. Epub 2011 Apr 15. PMID: 27867243; PMCID: PMC5115875.

- Klevens J, Barnett SB, Florence C, Moore D. Exploring policies for the reduction of child physical abuse and neglect. Child Abuse Negl. 2015 Feb;40:1-11. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.07.013. Epub 2014 Aug 12. PMID: 25124051; PMCID: PMC4689429.